Sound investments

Now that you've spent a fortune on CDs,

listen to this: Music sounds better on vinylBY BRAD KAVA

Mercury News Staff WriterA COUPLE of months ago I put a new version of a classic Muddy Waters album into my compact disc player and something terrible happened.

Waters' booming baritone was a revelation as it jumped out of my speakers. Buddy Guy's sinuous guitar sounded like it had a life of its own. Willie Dixon on bass and Clifton James on drums seemed to be standing there — right there — in the corner of my living room.

The sound was truly wonderful. But I felt terrible.

All of a sudden, listening to "Folk Singer," which was recorded at a Mississippi plantation in 1963, I realized that I'd been hoodwinked again.

For more than a decade, recording companies have been lying to us. They told us to throw away our records because compact discs had perfect sound. Then these executives, who once boasted that eight-track tapes would be here forever and quadraphonic sound was the wave of the future, virtually stopped selling and making records and left us little choice but to go digital.

I bought into it for a while. After all, compact discs were more compact, convenient, louder and brighter than records.

But this disc, cut 21 years ago and recently re-released on an audiophile 24-karat gold CD, sounded better than anything I've heard in years.

I looked disdainfully at my wall of CDs, some 400, bought at about $15 each, and I knew that not one of them sounded this good.

I called my friend who had recommended the Muddy Waters disc to tell him how great it sounded. He had even worse news.

"That's nothing," he said. "Wait till you hear the record."

The what?

It's been 15 years since digital music went mainstream, but for the breed of listeners who call themselves "audiophiles," the argument has never stopped.

They have been standing alone in a corner at the party, ranting about compact discs like a health food fanatic at a celebration of the Twinkie. Although most "record" stores don't carry records anymore, these fanatics claim digital discs are an assault on the ears, that numbers can never truly capture the intricacies of voices, strings and horns, and that vinyl is a warmer, more realistic medium for the reproduction of music. One vinyl extremest, Michael Fremer, music editor for the audiophile magazine "The Absolute Sound," suspects record companies quickly did away with vinyl partly so that consumers wouldn't be able to make the comparison.

I've listened to their complaints for years, but until hearing the Muddy Waters album, I never had reason to put it to the test.

Then, last week, I got a chance to do it in a big way. I hooked up with Herb Belkin, the owner of Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, a Sebastopol company that sells audiophile CDs for $30 a pop and has just started making records again for $25.

Here is someone who is intimately familiar with both forms. And someone who has devoted the latter part of his life to shooting for an impossible goal — making records or discs that sound as good as live performance.

A lot of reviewers say the rock, jazz and pop discs his company has put out come closer capturing the magic of recording than any other.

Belkin, 55, stumbled into the music business. An attorney who grew up in the Bronx but studied in Lincoln, Neb., he says his life has been a series of accidents that left him in the right place at the right time.

For example, as a street tough in New York who got a University of Nebraska football scholarship, he made a geographical mistake when he chose the Midwestern school. He thought Nebraska was in the Southwest, near Arizona. He learned otherwise.

The cold and the Beaver Cleaver down-homeness of the Midwest led him down a path he never would have followed had he stayed in New York. He put aside the street punk scene of the Bronx, cut down on football and began studying law.

He ended up in Washington, D.C., in 1963, an early specialist in equal-employment law. He worked for the Justice Department but left when Richard Nixon was elected and did employment law work for entertainment companies, including NBC and Capitol Records.

During a wave of cutbacks in the industry, he soon found himself taking on more and more roles at Capitol Records. He began negotiating contracts with artists, and then was put in charge of finding new artists. Among his discoveries were Grand Funk Railroad, the Rasberries and Manhattan Transfer.

Pretty soon he was ensconced in the talent end of the business and couldn't get out, even when he wanted to go back to law. He began working at ABC Records in the 1970s.

One day in 1977, for no reason he can figure, he let two guys into his office to pitch their high quality sound-effects albums. They wanted to produce better quality recordings than were being issued by conventional record companies, and they asked for the rights to some ABC artists to show what they could do.

Like most record execs, Belkin didn't know much about recording technology, but when they talked about the large profit margin to be made on high-quality discs for high-end audiophile consumers, he understood that.

When the two entrepreneurs — Brad Miller and Gary Giorgi — returned with an audiophile version of saxophonist John Klemmer's "Touch," Belkin said he was sold on the sound.

Soon after, he got the rights to do a high-quality version of Pink Floyd's "Dark Side of the Moon," one of the best-selling discs in recording history, for Mobile Fidelity. It opened up a new market for the record company, which sold the discs in stereo stores. The company has sold more than 300,000 copies of "Dark Side" on record, real-time cassette and gold compact disc.

Belkin's handling of sound quality is so revered that the limited pressing of 25,000 Beatles boxes he did in the early 1980s has jumped in value from $300 apiece to more than $3,000.Take your pick

So I asked Belkin, the master of the master-tapes, which he liked better: CD or vinyl.

"There is no question," he says. "Let me put it to you this way: CDs are like pornography; vinyl is like actual sex. Someone else said that our gold CDs take you into the control room of Muddy Waters' studio. Vinyl is like being in the room with him."

In a blind test, with good stereo equipment, Belkin says he will pick the vinyl recording over the digital every time.

Belkin says the problem lies in the nature of digital recording, which basically translates a recording made on magnetic tape into a series of numbers that are stored on a disc and are then translated back to music on your compact disc player.

"Digital is clean and convenient but it isn't musical," says Belkin.

The digital vs. analog argument has been going on since compact discs were introduced in the early 1980s.

The record company and press fanfare said the new medium was a perfect way to capture music and reproduce it.

On relatively inexpensive stereo equipment — boom boxes, Diskmans or even mid-priced stereos — compact discs sound better than records.

Some instruments sound clearer, punchier, brassier, more brilliant. And, most importantly, the Rice Krispies guys are gone. No more visits from snap, crackle, pop or hiss, who regularly interrupted some of the best moments on vinyl.

But, Belkin says, on high-fidelity systems — stereos with sensitive components valued at $2,500 or much more — records have more depth and a warmer, silkier sound. And on systems with good turntables — and with records carefully maintained — much of the distracting noise of vinyl is gone.Music by numbers

"Digital isn't a hi-fi medium, it is a mid-fi medium," says Belkin.

Because it is computerized music, digital sound also grows tiresome, he adds.

"I don't think anyone will own up to this, but I think it is fatiguing, for the same reasons you get carpal tunnel syndrome or you can't sit in front of cathode ray tubes for too long. It is a medium we don't understand fully and it has a physiological effect."

And he says, the proliferation of digital has changed a generation's listening habits. Youths who have only heard digital don't listen to music as long as their parents raised on vinyl did, he says. Most of them listen to a disc fewer times or listen to a few tracks.

Unless they have heard vinyl, most of them don't know what they are missing, he says.

There are musicians, including Neil Young and Keith Jarrett, in Belkin's corner. Young says that digital recording has stripped the soul from his songs and filtered out much of the feeling. Pianist Jarrett says that although digital does reproduce the note precisely, there is more to the note than is captured digitally. There is the room it's recorded in and a dissonance that lingers after a note that is lost in digital recordings.

Other musicians say they prefer digital. Guitarist Trevor Rabin of Yes likes it so much he recorded his last release on a series of MacIntosh computers, rather than using tape of any kind. (Many digital recordings are taped on analog recorders and then converted. Some are taped on digital recorders.)

He says he doesn't think the human ear can detect the range of sound that analog audiophiles say they are missing.

"To me the argument is gobbledy-gook," says Rabin. "If you analyze what analog tape is, it is information and in a crude way bunches of rust stuck on plastic tape. It goes over the recording head and a magnetic field appears and changes rust from positive to negative and draws crude wave forms. It is less sophisticated than digital, which draws very accurate numbers."

Belkin makes another argument. He says in making an analog record, you can play music in every stage of the process. The tape, the master disc used to press the vinyl, and the vinyl with its grooves — all make continuous music. You can play a master or vinyl disc even with a nail, and make some kind of music. In digital, however, you have to translate the music to numbers, a process, he says, that strips it of life.

"It's like the movie 'The Fly,' " he says. "Jeff Goldblum would go into that convertor, and his molecules would get jumbled around and you never knew what would come out. That's digital."

So why is a guy who hates digital making it? And what is the future for those of us who have sunk too much money into too many music forms only to watch them be replaced?

"This is the Grail," says Belkin. "We keep trying to find perfect sound, but it's an impossible task. But that's the challenge I keep coming back to."Quick, cheap, radio-ready

He says it is a challenge that few major record labels bother to take. Many of their executives came from the world of radio and are used to music through a two-inch speaker. They want to produce music that is punched up and sounds bright on the radio. Not music that can be listened to repeatedly.

They also want to make music as cheaply as possible. And, because compact discs can be made more quickly and have fewer returns because of defects, they can be made far more economically than records.

Record companies spend roughly $1.50 to manufacture a disc or record, Belkin says. Much of the markup is to sign and promote artists. Belkin's slower process costs from $4 to $4.50 to manufacture records or discs.

Belkin has watched his company's fortunes plummet and rise with the compact disc. In the late '70s, he made audiophile records and grossed around $10 million. Then, with the publicity surrounding the disc in the early '80s, his gross dropped to $2.5 million. He took it back up again, slowly, to around $10 million by releasing gold compact discs made with the best possible sound quality.

Unlike other companies that only used their best recording techniques for classical or jazz, Mobile Fidelity's 26 employees have produced a line of audiophile rock discs, with a large stable of artists including Eric Clapton, Santana, Cat Stevens, Elton John, Alan Parsons, the Who, and the Moody Blues.Fat records

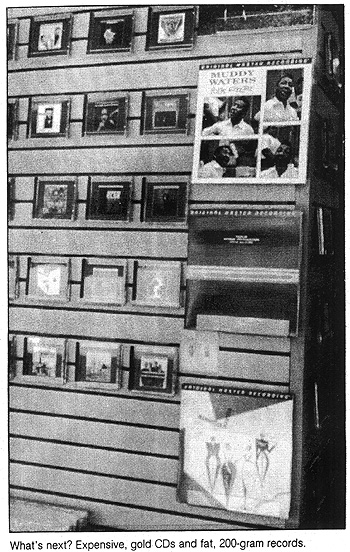

This year, Belkin had two big announcements at the Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show. One was of a new series of discs, made with a digital-to-analog converter that is said to capture more of the music than converters used by other companies.

The other is of a return to vinyl, with the company making extremely thick and good-sounding 200-gram records. (Records were about 120 grams when they were last popularly made.)

The discs are made with what is called the GAIN system, short for Greater Ambient Information Network. The company says it gives a more complete sampling of music than faster systems used by major record companies.

Basically, every CD is a compilation of 16 bits, with 65,536 samples of the music on each bit. Many convertors sample part of the music and project where a note will go, rather than sampling the entire note. The GAIN system, developed to guide missiles and do CT scans, where one can't afford to miss a sample, is said to give a more complete reproduction of the music.

Belkin says the CDs are far from perfect, but they are the best he can do. (The gold, incidentally, has nothing to do with the audio reproduction, but is longer lasting and harder to damage than the aluminum in conventional CDs.)

His real pet project, however, is making good-sounding records for "the tenth of one percent of music buyers who are audiophiles." He says he is like an antique dealer, dealing in a small percentage product for people who still love the old ways.

And, he notes, the vinyl market is growing some. Pearl Jam's newest release sold 50,000 copies on vinyl, long after most record companies had given up on the medium.

Nirvana's Kurt Cobain preferred it and word of its more lively, more direct sound is spreading to a new generation of listeners.

By making thicker, 200-gram vinyl records, Belkin hopes to re-introduce the best possible sound to people who have grown tired of "digital assault."

"We spend a fortune trying to make CDs that sound like records," he says. "Now we can give them the real thing."